What if…”Jesus only had seven followers?”

On ambition, survivorship bias, and playing to empty stadiums

Hello!

Warning: what follows is a hard pivot from the other day’s holiday romcom romp. That being said, this is a reminder that my inbox is always open to discuss the narrative choices of the Princess Switch film trilogy and similar subjects.

Six months ago, I opened a doc and pasted a quote from TikTok star Addison Rae. She was featured in the summer issue of Interview, and in between riffing about Britney Spears and the transformative power of wigs, editor Mel Ottenberg asked Rae if there’s such a thing as too many followers? Her answer:

“I mean, you know what they say: Jesus only had seven followers.”

I took a screenshot of the Instagram promo post with this pull quote and sent it to several friends who also make stuff and struggle with how the attention economy forces all artists (lone exceptions for the very wealthy and very well-connected) to also be influencers. We collectively groaned, laughing at Rae’s absurdity. It was easier to put on the crown of delusion for a few minutes than to go too deep on the fraughtness of building a “following” as part of building an art practice.

(I’m separately dying to know which four of Jesus’ twelve disciples did not make the cut on the list. Like Judas, sure. But who else? What gossip does Addison Rae have here that the rest of us do not? And who are “they” in “you know what they say?” Because I didn’t know that, Addison! I’m still frustrated that Ottenberg asked no follow up, moved right along to a yes/no question about TikTok.)

But anyway, back to the present. It’s December. Year end lists abound, and regardless of how much I want to resist, I am nothing if not a sucker for the annual performance review. And in my first moments of self-flagellation, I remembered, of all things, “Jesus only had seven followers.” This document I returned to, titled “audience x addison rae” was filled with a handful of other things I have limited-to-no memory of saving. Things I will share with you shortly.

The summer version of me thought it was all about “audience.” I had been wallowing in the feeling of writing a ton, only to be read by only a handful of people. Even typing that makes me sound like a total twat, coming face to face with how writing books works. You write tens of thousands of words on spec, hope one day it all works out, and have to largely play coy and cagey about it all until then. That’s not even the most embarrassing part though. No, the worst bit is admitting why it’s uncomfortable: the gaudy desire, buried beneath all the work, to be read in the first place. Some writers give off a vibe that readership does not matter to them, that the writing is merely about getting the words down. For me, writing is about connection, and I am already more than sufficiently connected to myself. But it’s quality over quantity. Like Jesus via Addison Rae, seven would be fine!

Around that same time, I listened to an interview with author Rita Bullwinkle on Brad Listi’s podcast. She described writing as “solitary and rigorous and obsessive.” As “playing to an empty stadium.” She spoke about how no level of success will ever compensate for the amount of work required to do things like write books. A horrifying realization, but one she was accepting of, had even found solace in, specifically in passing back and forth the desperate gems of vulnerability with fellow writers. Bullwinkle described herself as “desirous” rather than ambitious.

I nodded my head, especially over that last bit. Of course. Desire not ambition—that would be the cure for my neurosis.

But Rita Bullwinkle’s Headshot went on to be nominated for The Booker Prize. For the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. To be listed as a Best Book of 2024 by NPR, Vulture, The New York Times, The Guardian. You get it, what Rita Bullwinkle and Addison Rae have in common. It’s easy to say “Oh, it doesn’t really matter.” when you have “it.” Or at least that’s how I imagine it, but who am I to say that Rita and Addison aren’t just staring down a new mountain of achievement to climb?

In that same old Google doc, I had also saved a quote from Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and educator Jericho Brown:

“We must write as if we know we’ll never win any awards for it, or we must write as if we’ve already won all the awards for it…If no readership or awards come, then I don’t even notice because I understood all along that I wouldn’t get them or that I already had all of them. The thrill is always the act of writing itself.”

Another case of, “Yes, sure. Amen.” But beneath the way I intellectually agree with this, a grimace blooms. It has to become easier to say these things once you’ve succeeded at scale, no? Or do we just not care to read them from those still firmly in their flop era? Is it even a flop era if you never escape it? Lately, in my darkest moments, I can’t help but wonder. Again, it’s so mortifying to even record this, to not be standing in power-pose, sparking with the sheen of survivorship bias, my markers of success beaming behind every word. But over the last year, I’ve learned how publishing is a lot of waiting around, holding back endless mundane details, and trying to convince well-meaning people in your life that some failure is fine, actually.

There’s a movie called Showing Up where Michelle Williams plays a ceramics artist who spends her days sulking around and making art she believes in, to little acclaim. The tone is slow, languid, filled with little quips of insecurity and jealousy, of deep sighs. It ends with her not experiencing any kind of personal or professional victory, but by a kiln accident, a tiny audience at her opening, and a rogue pigeon who destroys her work. The creative process! But even then, as she leaves the gallery to buy a pack of cigarettes while the credits roll, it doesn’t feel “over.” In my gut, I know she’s waking up the next day, or maybe the next week with a new idea, that she’ll keep going despite the mediocrity. Despite her family giving her looks that beg, “Have you considered pursuing something we have a better societal script for? Or maybe just succeeding, more quickly, at whatever this is.”

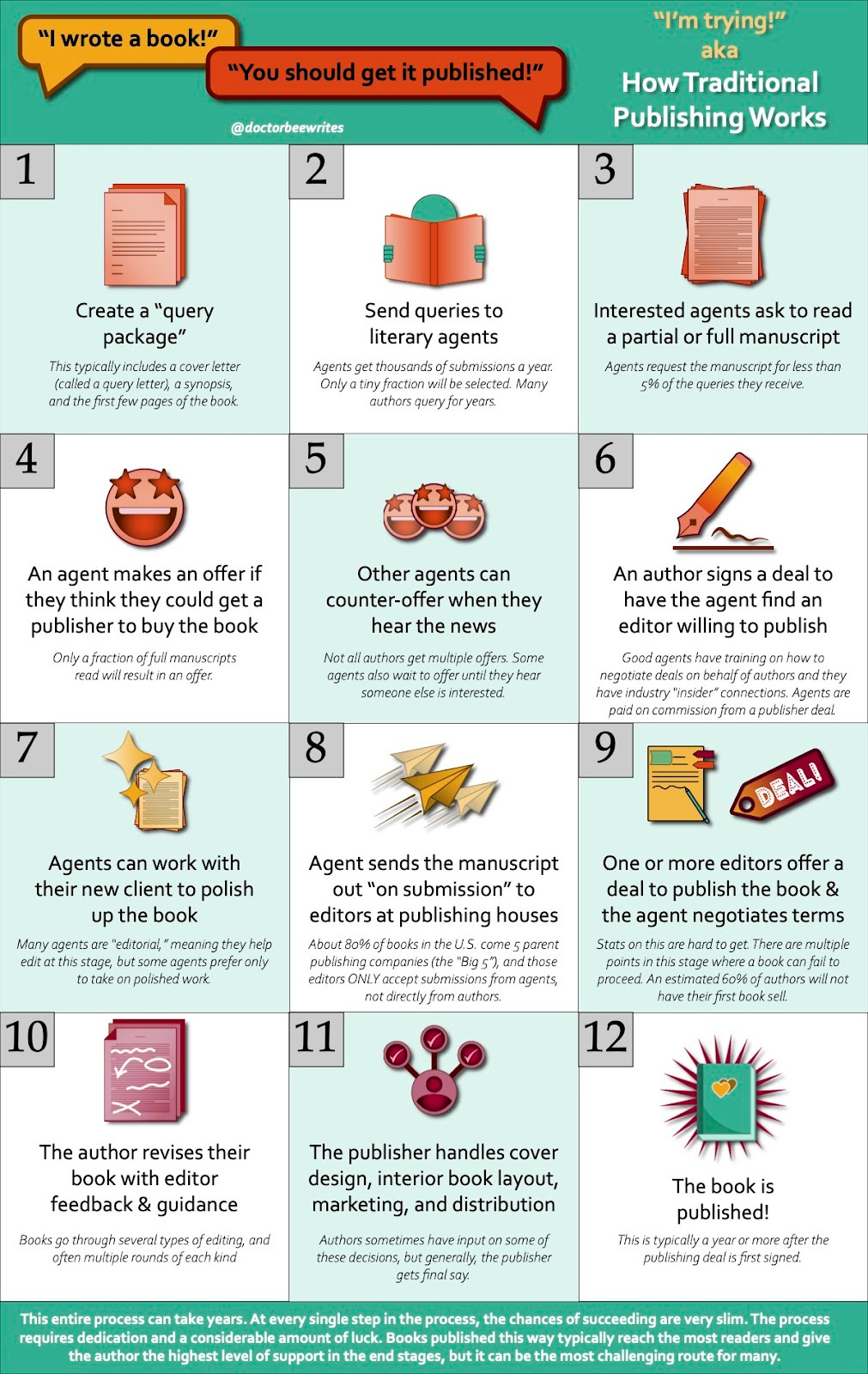

The hardest part of all of this (beyond explaining how traditional publishing works, but I now have the above graphic for that) is trying to transmute artistic compulsion. Whether the flop era comes, goes, returns every eighteen months, etc.—I will still be here making things. There’s maybe even something freeing in recognizing that, in accepting that it’s happening whether I want it to or not. Even if I take away writing, I now know myself well enough that it’ll just turn elsewhere.

Last week I read a memoir called Ambition Monster. It’s another entry in one of my favorite genres: nonfiction with a “divorce your self-worth from your job” thesis, like Work Won’t Love You Back, Bullshit Jobs, and All The Gold Stars. The author, Jennifer Romolini, carves an “anti-girlboss tale” in which she explores how unresolved trauma became workaholism, and how she later gave up sacrificing her soul to meet never-ending corporate demands as a means of personal validation. Getting fired from her high-powered C-Suite job definitely began her radicalization, but I’m not here to litigate that. What I’m more interested in is what happened next. The book has no epilogue. That same firehose of workaholism and people-pleasing and perfectionism was seemingly turned toward an endless channel of personal creative work (like writing Romolini’s book) versus responding to Slack messages. Ask me how I know about this presumed pivot!

I thought that by taking a year off from pitching other writing and channeling that energy into book-length projects, I might learn patience. I would emerge a book writer who was zen, who believed that it would all work out on the universe’s timeline, who thought in years rather than days. Instead, I just uncovered more fully the rot that was already there—without the quick highs of completion and publication, I had to sit longer with my creative compulsions, wallowing in the “why” of it all. I did fall in love with writing books, though, so for better or worse, there’s that.

Maybe the real lesson learned here is that it’s impossible for anyone to make art (or at least art that’s interesting) without being plagued by big feelings and a bubbling vat of neuroticism. For now, that is the lie I will be telling myself. Feel free to borrow it if it serves you.

Just like the time I wrote about trying and failing to rest, I know I don’t yet have the hindsight to give a crisp verdict here. Part of me doesn’t even want to hit the publish button, viscerally aware of how mucky this all is. But it’s neat to recognize that it’s that same specific part of me who has been challenged this year, who knows how high the bar is. But there’s also the tender part of me, the one who remembers that every time I share something that feels too personal and messy, I end up having the kinds of conversations I didn’t realize I was starved for until they happen.

So anyway! Please report back if you’ve figured this stuff out, or if you’re also on the endless train to tender town.

<3

This newsletter brought to you by:

The Princess Switch 3: Romancing The Star

A homemade chocolate chip cookie via this no-chill, no-mixer recipe.

Reed, Hannah, Kayla, Emory, Christin, Rachel, and Elena for reading some truly beefy Word docs.

If you’ve made it this far, you! For being one of my “seven followers” and for letting me be an earnest and maybe even unlikable narrator.

I would like the be one of your seven followers! Loved this read and felt it deep inside my bones/ligaments/etc. Appreciate you sharing something mucky — you are not alone 🙏